Make-up May-Oo at work (in one of the above pictures, he is seen next to the founder of the Free Burma Rangers ex-Major David Eubank (formerly US Special Forces) in the Karen National Liberation Army.

မိုးမောက်မြို့နယ်အတွင်း အလော့ဘွမ်တောင်ခြေဒေသဖြစ်သော မြို့သစ်တာဝါတိုင်နှင့် ဆလောင်ကုန်းအရှေ့ဘက် တောင်ကြောတစ်လျှောက်တွင် တိုက်ပွဲအပြင်းအထန်ဖြစ်ပွားခဲ့ခြင်းဖြစ်ပြီး စစ်ကောင်စီတပ်ဖွဲ့ ဝင် ၂၀ ဦးသေဆုံးခဲ့သည့်အပြင် လက်နက် ၁၈ လက် သိမ်းဆည်းရမိခဲ့ကြောင်း အထက်ပါ KIA အရာရှိက ပြောသည်။

တပ်မ ၇၇ အထိနာခဲ့သဖြင့် စစ်ကောင်စီက ယမန်နေ့တွင် ခြောက်ကြိမ်တိုင် လေကြောင်းမှ လာရောက်တိုက်ခိုက်ခဲ့သော်လည်း KIA ဘက်မှ ထိခိုက်မှုမရှိကြောင်းလည်း ၎င်းက ဆက်လက်ပြောကြားသည်။

မိုးမောက်မြို့နယ်ဒေသခံတစ်ဦးက “တပ်မ ၇၇ ကအယောက် ၂၀ သေပြီး သေနတ် ၁၇ လက်ရတယ်။ အလော့ဘွမ်တောင်ခြေ မိုးမောက်တာဝါတိုင်နားက တိုက်ပွဲမှာ။ သူတို့ (စစ်ကောင်စီ) လည်း အလော့ဘွမ်ကို မရရအောင် ပြန်သိမ်းဖို့ ကြိုးစားလာတဲ့အပေါ်မှာ KIA ဘက်ကလည်း လက်မလွတ်အောင်ဆိုတဲ့ သဘောမျိုးနဲ့ ထိန်းချုပ်နိုင်အောင် တက်လာတဲ့ စစ်ကြောင်းတွေကို ခုခံပြီးမှ တိုက်ခိုက်နေတဲ့ သဘောအသွင်ဆောင်ပါတယ်" ဟု Myanmar Now ကို ပြောသည်။

ရန်ကုန်မြို့တွင် စစ်အာဏာရှင်ဆန့်ကျင်ရေး ငြိမ်းချမ်းစွာ ဆန္ဒပြသူများကို အကြမ်းဖက်နှိမ်နင်းခဲ့သည့် တပ်မ ၇၇ ကို ကချင်ပြည်နယ် အလော့ဘွမ်တောင်ခြေတိုက်ပွဲအတွင်း တပ်ပျက်သည်အထိ အထိနာခဲ့သော တပ်မ ၈၈ ကို စစ်ကူသွားရောက်ကာ ထိုးစစ်ဆင်းခဲ့ခြင်းဖြစ်သည်။

Read the full news story here.

Myanmar's control of Covid-19 collapses after coup 03:24

Rising food costs, significant losses of income and wages, the crumbling of basic services such as banking and health care, and an inadequate social safety net is likely to push millions of already vulnerable people below the poverty line of $1.10 a day -- withwomen and children among the hardest hit.

Analysis from the UN Development Program (UNDP), published Thursday, warned that if the

does not stabilize soon, up to 25 million people -- 48% of Myanmar's population -- could be living in poverty by 2022.

That level of impoverishment has not been seen in Myanmar since 2005, when the country was an isolated, pariah nation ruled by a previous military regime, it said.UNDP administrator Achim Steiner said it is clear "we are contending with a tragedy unfolding."

"We have fractured supply chains, (disrupted) movement of people and movement of goods and services, the banking system essentially suspended, remittances not being able to reach people, social safety payments that would have been available to poorer households not being paid out. These are just some of the immediate impacts," Steiner said. "The protracted political crisis will obviously worsen this."

April 30, 2021

Yangon, 27 Apr 2021

A few days ago, brief hopes were kindled that Myanmar’s military, currently engaged in a campaign of violence and intimidation against persistent protests since the February 1 coup, was considering steps toward easing its crackdown.

At the April 24 summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Myanmar’s military leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, appeared to agree with the group on “five points” of consensus. These included “an immediate cessation of violence in Myanmar” and “constructive dialogue among all parties” and that ASEAN would provide humanitarian aid and appoint an envoy to mediate. The language was weak and vague, but some governments took the document as an encouraging sign the regime was turning toward an exit ramp.

Two days later, the junta issued a clarifying statement quashing that hope. The junta said it will give “careful consideration to constructive suggestions made by ASEAN Leaders when the situation returns to stability in the country since the priorities at the moment were to maintain law and order and to restore community peace and tranquility.” ASEAN points of “consensus” are now “suggestions” to be considered at some indefinite future point.

Make no mistake: The junta statement is a crisp slap in the face to ASEAN members and their allies. Min Aung Hlaing, who besides leading a coup that overturned Myanmar’s democratic elections oversaw a military accused of crimes against humanity and genocide against Rohingya Muslims, played ASEAN leaders for fools.

Perhaps there is a silver lining. In abandoning any semblance of concession, the statement forces ASEAN and other governments to acknowledge the realities of the situation: The junta has shown no intention of taking meaningful steps to curtail abuses. This is nothing new. Myanmar’s military, which has ruled the country with a heavy hand for most of the last 60 years, has no history of making meaningful concessions to ASEAN.

Since the ASEAN meeting, the security forces have continued to threaten and arrest demonstrators. The junta has warned civil servants to return to work or face severe consequences. The leadership has done nothing to dial back its confrontational rhetoric.

The ASEAN summit’s failings demonstrate that standard diplomatic protocols are insufficient to deal with the Myanmar leadership — who are, after all, not diplomats but generals. The international community needs to speak to them in a language that even they will understand, using coordinated, targeted financial sanctions that will directly and significantly affect the military as an institution and its leaders as individuals.

While some governments have imposed economic sanctions on the junta leadership and a few of its companies, these measures haven’t been targeted enough to get at the junta’s main sources of income. Governments now need to take far tougher action to complement the courage shown by Myanmar’s Civil Disobedience Movement and demonstrate to the junta that the consequences for its brutality will only get worse.

Governments need to focus on stopping the junta’s access to foreign currency revenues, which are collected in overseas bank accounts as proceeds from selling the county’s natural gas, gemstones, valuable metals, stone, and teak wood. On top of simply sanctioning junta companies, governments should block transactions and freeze the bank accounts into which foreign revenues are paid, most of them held in the name of Myanmar’s Foreign Trade Bank. These targeted measures can be tailored to allow vital services provided by international companies to continue — for instance, gas production, operations of ports, and transportation services — while keeping the proceeds of those services out the military’s hands.

Stopping offshore foreign currency revenues also alleviates most concerns about negative humanitarian impacts on the people of Myanmar. As several independent groups focused on extractive industries transparency have documented, most of the money in question isn’t going to the Myanmar people anyway; it’s being stolen from them by the military leadership. Concerned governments might as well seize and hold those funds until they can be repatriated to a legitimate government for the benefit of the nation.

But to make these sorts of measures work, governments need to work together, coordinating law enforcement, intelligence, and monetary authorities across multiple jurisdictions. It will be challenging to chase down the dark money and the offshore accounts and enforce legal measures across different jurisdictions. It may also take time for consequences to lead to changes in policies and practices. Squeezing the junta’s cash sources, however, could be the only real strategy with a chance of pressuring the junta to restore democratic, civilian rule.

That’s why so many protesters in Myanmar are asking for stronger international sanctions: They know that only the very toughest of measures is going to get the junta to back down.

A Myanmar activist posing for a campaign photo.

Maung Zarni, FORSEA, 26 Apr

An in-depth Facebook LIVE discussion – a post mortem discussion – on the Five Point Consensus from the recent ASEAN Summit on Myanmar with views from three top discussants: Tan Sri Dr Sayed Hamid Albar, Professor Michael W. Charney, and Dr Khin Zaw Win.

FORSEA Dialogue on Democratic in Asia hosted an in-depth Facebook LIVE discussion – a post mortem discussion – on the Five Point Consensus from ASEAN Summit on Myanmar (Crisis) hosted in Jakarta by Indonesian President Jokowi on 24 April.

The three discussants were Tan Sri Dr Sayed Hamid Albar, currently adjunct professor of international law at Malaysian national university UKM and former Foreign, Defence and Home Affairs minister, Professor Michael W. Charney of the School of Oriental and African Studies at London University and Dr Khin Zaw Win, prominent democrat, former political prisoner and human rights activist heading Tampadipa thinktank in Yangon.

The Malaysian scholar, diplomat and politician Dr Albar pointed out the fundamental problem of the summit being that ASEAN is a good platform for stability and economic development, but it is in the uncharted territories with Myanmar is undergoing nothing less than total social and political revolution.

Professor Michael W. Charney offered a historical perspective from other civil war or revolutionary situations wherein communications with the oppressive militaries were meaningful only when the killing machine was vastly weakened and the militarists were no longer in control of the turn of events (against them). Besides, Charney spoke about the practical need for building alternative institutions such as the Federal Army – very much in popular demand among the public in Myanmar – which goes beyond coordination among different existing Ethnic Armed Organizations, created for self-defence of their respective communities.

Speaking from Yangon, the Burmese dissident Dr Khin Zaw Win observed pointedly the complete disconnect between international experts and diplomats and the overwhelming public opinion on the ground in terms of how a single reality – a society on the cusp of the Zero-Sum Revolution against the national military that has morphed into “nothing but armed terrorist gang”. He took issue with the view that the Burmese military is a part of the solution, and therefore must be a part of the problem. For the Burmese society is engaged in the secular equivalent of excommunicating the Tatmadaw or military totally while undergoing a transformative process of becoming inclusive and communal – as opposed to racist and divisive.

Using the medical analogy the FORSEA host Dr Maung Zarni characterized the murderous military called Tatmadaw as the cancer in Myanmar’s politics, economy and society, hence the removal of it for Myanmar patient to live on. He pointed out the need for ASEAN and international diplomats to understand and appreciate the Burmese people’s grounded view and analyses of their own predicament under the boot for 3-generations since 1962.

Private Meeting on Myanmar via VTC

This morning (30 April), the Security Council will hold a private meeting on Myanmar via videoconference (VTC). The expected briefers are Special Envoy for Myanmar Christine Schraner Burgener and Erywan bin Pehin Yusof, Second Minister of Foreign Affairs of Brunei Darussalam, as the Chairman of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Draft press elements were circulated to Council members late yesterday (29 April), but at the time of writing, it is unclear if members will be able to agree on them following the meeting.

A private meeting of the Council is closed to the public. However, a private meeting differs from Council consultations, which are also closed, in being a formal meeting of the Security Council. In addition, in line with rules 37 and 39 of the Council’s provisional rules of procedure, member states whose interests are directly affected and Secretariat officials may be invited to participate in a private meeting. The rules of procedure also require that a communiqué be issued following a private meeting, unlike consultations, for which no written record is created. Such communiqués habitually note that the meeting has taken place, and who attended and briefed.

Read the full story here.

Killing, Airstrikes and Displacement Continue, With 25,000 People Displaced as the Burma Army Steps Up its Attacks in Northern Karen State

27 April, 2021

Karen State, Burma

SOURCE: Free Burma Rangers

Dear friends,

This report is an update on the increasing attacks in Karen State, Burma, as well as a story by one of our team about children being killed here by the Burma Army. Killing continues in Karen State as the Burma Army moves troops and armored vehicles towards Butho Township, Papun District, northern Karen State. 25,000 people are now displaced. The Burma Army, while trying to resupply its camps, mortars villages daily and today, 27 April, the Burma military resumed airstrikes, dropping five bombs near Bwa Der and Dagwin villages in Butho Township, Papun District. This has pushed the number of IDPs from 24,000 last week to 25,000 today. At the same time, in the cities, the Burma Army continues to kill and hunt down protestors, killing over 750 people. Air strikes by Burma Army fighter jets have now begun targeting civilians in Kachin State as well. Below are new reports on Burma Army attacks in Papun District of Karen State.

12 April 2021, Lay Poe Hta Village Tract, Dwelo Township, Papun District: Burma Army Military Operation Command (MOC) 8, Light Infantry Battalion (LIB) 407, killed two civilians, 50-year-old Saw Pah Kay and 35-year-old Saw Nge Lay. They were killed by a Burma Army ambush along the road between Neh Ka and Wa Tho Koh villages.

On 12 April 2021, at 18:00 local time, Infantry Battalion (IB) 19 from Papun shot mortars into Doo Peh Lki Per He Kla Village. Villagers abandoned their homes and fled into the jungle.

On 13 April at 15:00 local time, in Ka Po Klah Village, Butho Township, Papun District, five villagers caused a land mine to explode. The explosion caused the death of Way Koo, and wounded four others: Thoo Taw, Pah Per Tha, Sa Lo Gyi, and Ng Pin.

On 13 April, 10:00 local time, Burma Army MOC 8, LIB 401, took security along the road between Kaw Pu and Ka Hee Kyo, Butho Township, Papun District. As their resupply trucks moved along the road, they mortared into any nearby villages to clear any resistance.

On 14 April 2021, 10:00 local time, MOC 8, LIB 410, from Hoh Kyo Koh camp in He Poe Der Village, Butho Township, Papun District, fired mortars into Mae Thaw Kee Village.

On 15 April 2021, at Htwe Thee U Village, Dwelo Township, Papun District, 195 new IDPs fled their village after they were threatened by Burma Army. In Ta Thoo Kee Village, 140 villagers fled their village as well. They fear for food and have had to abandon their farms.

On 17 April 2021, Saw Hsa Ri from He Poe Der Village, Butho Township, Papun District, lost his house after a Burma Army mortar round was fired by MOC 8, LIB 410. The round exploded in his house causing it to catch fire and burn to the ground.

On 17 April 2021, at Ta Keh Der Village, Luthaw Township, Papun District (GPS: 47Q LA 89714 60390), all 114 villagers fled out of the village as new IDPs as Burma Army mortared their village and moved troops near the village.

On 18 April 2021, the Burma Army moved 50 troops and four armored vehicles into Ka Ma Moung camp near Pa Heit Village, Papun District, to reinforce BGF Battalion 1014.

On 19 April 2021, the Burma Army sent 100 soldiers on patrol from BGF Battalions 1011, 1012, 1020 from Kaw Daw camp down into O Daw Village.

On 20 April 2021, 09:40 local time, soldiers from the Burma Army camp at Oo Thu Hta shot 10 rounds from an automatic weapon at civilian boats moving along the Thai/Burma border. No casualties reported.

On 20 April 2021, at 16:30 local time, a Burma Army fighter jet flew over Pah Nay Pah Koh Village, Luthaw Township, Papun District.

On 20 April 2021, 1035 local time, Burma Army LIB 20 fired mortars into Pah Gaw Lu Village, Luthaw Township, Papun District. Five rounds impacted in the farms of villagers.

On 20 April 2021, at 15:00 local time, Burma Army MOC 4, LIBs 704 and 709 from Kaw Daw Koh camp moved and set up a new outpost camp near Doh Kah Wah Kyo Village, Luthaw Township, Papun District.

Children Being Killed by Burma Army

The following is a personal reflection from a Free Burma Ranger team member.

Most of the children I know in Karen State don’t know who Min Aung Hlaing is. Most of them don’t really understand coups and what happens during a coup. None of the children I know in Karen State have fought the Burma Army, or even really know how to hate the Burma Army. But what they do know now is fear. Burma Army fighter jets started their bombing campaign against unarmed civilians in the dark of night on 27 March 2021. Imagine just settling in to go to sleep in a quiet and peaceful village when suddenly out of the darkness comes a noise you’ve never heard before, a fighter jet tearing the sound barrier, and then the jet starts spraying bullets from its machine guns and dropping bombs. Imagine the chaos, the panic, the fear.

On that first night of Burma Army bombings, 5-year-old Saw Ta Blut Soe was killed. The killing of just one five-year-old should be more than enough for the international community to step in and do something. But it wasn’t.

Injured on that same night was 12-year-old Naw T’Paw. She was sitting on her father’s lap when the bomb landed nearby. One piece of shrapnel exploded through the wall of the house they were in and went directly into her father’s head, killing him instantly. Another piece of shrapnel grazed her ear and her face, wounding her.

The next day the jets returned and in the light of day targeted and bombed the local high school, as if they were searching for a place where children might be hanging out.

On 5 April 2021, Burma Army air strikes continued in Karen State, this time killing 16-year-old Saw Pah Dah Chit. He wasn’t a soldier; he was just a teenager trying to figure his place in the world like all 16-year-olds.

And as the Burma Army shifts their momentum to ground attacks, they have continued to wound and kill innocent children as they shoot mortars into villages. On 7 April 2021, 11-year-old Naw Mee Wee was wounded when small bits of shrapnel sprayed into her body.

A few days later, on 12 April 2021, Burma Army mortars caught 15-year-old Saw May Ka Lo Oo with shrapnel; he had to be emergency-driven in the back of a pickup truck to get medical care for his wounds.

And these are just the reports that our Free Burma Ranger teams have reported on and collected themselves. The General Strike Committee of Nationalities in Burma has reported 41 children have been killed in attacks by the Burma Army from February 1st through April 14th, 2021.

Forty-one children killed? How is this being allowed to happen? The Burma military that is killing these children actually have support and financial backing from other international powers, but the innocent civilians that are dying on the streets and in villages don’t. How is this ok?

My Karen friend Ma Nay has a two-year-old whose face lights up every time I come to stay with him. His son tries to say my name in English and loves to play and cuddle with me. My heart broke when I saw pictures of Ma Nay and his family hiding in a cave because Burma Army jets flew overhead. And yet, in the picture, his two-year-old is playing and smiling, resilient as ever. Resilient in a way that I don’t understand, but thank God for creating us to be that way.

We pray that the Burma Army stops killing children and we pray that all the people in Burma would be able to find peace and justice.

Thank you and God Bless You,

Free Burma Rangers

The 4-brothers who fought back against Myanmar’s army

“I don’t want my children to grow up in the situation that my generation and the older generations did."

- Moe (18), one of the brothers who fought back against the regime

Originally published in The Guardian

29 Apr 2021

The young men only had a moment to study the river before rushing into the waist-deep water. The brothers – ranging in age from 15 to 21 – were unfamiliar with the border area and afraid of being seen. On the run from Myanmar’s military, they pushed on into the Thaunggin River.

After just a few minutes of wading, they stumbled into no man’s land. Moments after crossing the river, three smugglers dressed in military fatigues met them. After handing over 6,000 Thai baht (US$200) and exchanging a few words, the smugglers led them deeper into the woods and then to safety in Thailand.

Three months after the military coup on 1 February, four Burmese brothers have told the Guardian of how they were inspired to join the fight against the military – and how their involvement in protests in Yangon that turned violent eventually forced them to flee at the end of March.

Myanmar demonstrators wearing black hold black balloons and pictures of the people shot dead by troops during a protest in Yangon on 5 April. Photograph: EPA

Safely outside the country, the brothers have given an account of brutal military repression and their decision to take the fight to the military in a bid to prevent further violence. Their journey would take them from peaceful protest in Yangon to petrol bombing police stations and running for their lives.

Lin*, 21,the eldest of the four brothers, said he had watched the coup unfold from his home in western Thailand, close to the border. Seeing the death toll mount amid growing military brutality he felt compelled to join the resistance movement, and soon his three younger brothers and two cousins from different parts of Myanmar followed him to Yangon.

At 15, Za* is the youngest of the brothers. He said he took part in the resistance because he wanted to stop the violence on the streets. “Look at how many people they have killed in the past two months. If we don’t do anything and just let it happen so many more innocent people will die,” Za said.

Joining the protests

The men met up in Yangon and for the first few days joined the peaceful protests. Soon, they became part of a nightwatch team protecting residential neighbourhoods from night-time raids by security forces. Armed with sticks and swords they say they helped women, children and the elderly move around safely.

As they continued to demonstrate, some teams of frontline protesters began discussing the possibility of hitting back, Lin says. “People started saying we need to fight back. But they didn’t know how, and they were scared.” Lin says he was concerned it was just what Myanmar’s military, also known as the Tatmadaw, was hoping for.

They told how they joined a small minority of protesters on the frontlines squaring off against security forces, using molotov cocktails and slingshots in what they said they believed was a legitimate form of self-defence against the military’s automatic weapons. But it was not without cost. During one attack on a police station, Lin says one of the team died after being hit in the head by a rubber bullet. He was in his 50s.

“I don’t want my children to grow up in the situation that my generation and the older generations did,” says Moe*, 18, another of the brothers.

The first attack

It was about 11pm when the group carried out its first attack on a police station.

Lin describes how they moved towards the building, with more people joining the group as they got closer. Some were carrying molotov cocktails, others were armed with slingshots and swords, he says. But when the men edged near to the police station, the group hesitated.

Lin says: “At that time I was aggressive, I was mad, no one was willing to throw the cocktail bomb. “I came back [to Yangon] thinking I was going to be a peaceful protester … but if I needed to be another thing, then I will be that, too,” Lin said. “So I took the molotov and went up to the [overpass] bridge.”

A protest sign appealing to the United Nations as part of a ‘bleeding strike’. Photograph: Facebook/AFP/Getty Images

The bottle landed right on top of a pile of rubbish leaning against the building. Flames started to shoot upwards towards the roof, Lin says. “We wanted to scare them,” he says of the Tatmadaw. “You make us feel unsafe, then we want you to feel unsafe too.”

Lin says a truck full of Tatmadaw soldiers arrived, and the group started retreating. Footage seen by the Guardian shows teargas rounds whizzing past them as they fled. The group could hear the sound of people celebrating in their homes as they sprinted past. “It was like we were coming back from war.”

Over the next few days, the brothers, along with a handful of other teams, targeted multiple police stations. Lin says he doesn’t believe they injured anyone in the attacks. They were unsuccessful in burning down the buildings. He says the attacks were psychological warfare and the men felt they had to show some degree of force to counter the military.

‘We had to run’

The campaign continued until the day Lin says they heard one of their friends had been abducted by security forces. “They contacted us and said he died. They tortured and killed him,” he recalls.

“We all had to run at that point. They said, ‘One of our guys is gone. We are on the run now. You should too.’” They agreed it was time to leave.

Mourners attend the funeral of Saw Sal Nay Muu, who died after attempting to flee a checkpoint manned by security forces in Dawei. Photograph: Dawei Watch/AFP/Getty Images

The brothers woke up early to begin their trip east to Hpa-An, the capital city in Karen state, close to the border with Thailand. The day after they left their apartment in Yangon, a neighbour told them police had searched it.

After laying low in Hpa-An for a few days, they finally got the call to leave. They would have to make the cross near Myawaddy, a town known for its casinos and entertainment venues. After just a few minutes of wading through the river, they stumbled into no man’s land. Moments after crossing the river, three smugglers dressed in military fatigues met them.

The smugglers demanded their payment upfront before they moved the brothers to a secret location. After paying the troops, the group hiked for another 20 minutes in the dark to a bunker where they were told to wait.

A protester, who was injured during a demonstration in Mandalay. Photograph: AFP/Getty Images

“We were afraid of them because they were strangers with guns and we were in their place,” says Htet*, 18, another of the four brothers. “If they wanted to do something they could’ve and we didn’t have anything to stop that.”

At around 3pm they were told it was finally time to go. They walked along a dirt path that would lead to a paved road, their guide told them. After more trekking on their own, they found their way out of the woods. They had made it.

The group crossed the border at a time when Myanmar’s military had killed more than 550 people and detained nearly 3,000, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

“It was a hard decision to make to come here. Even though we are safe and comfortable, we want to be back there. But it was just too dangerous,” Lin says.

“But the good thing was I had my brothers. I wouldn’t have been able to handle it alone.”

*Names have been changed to protect identities.

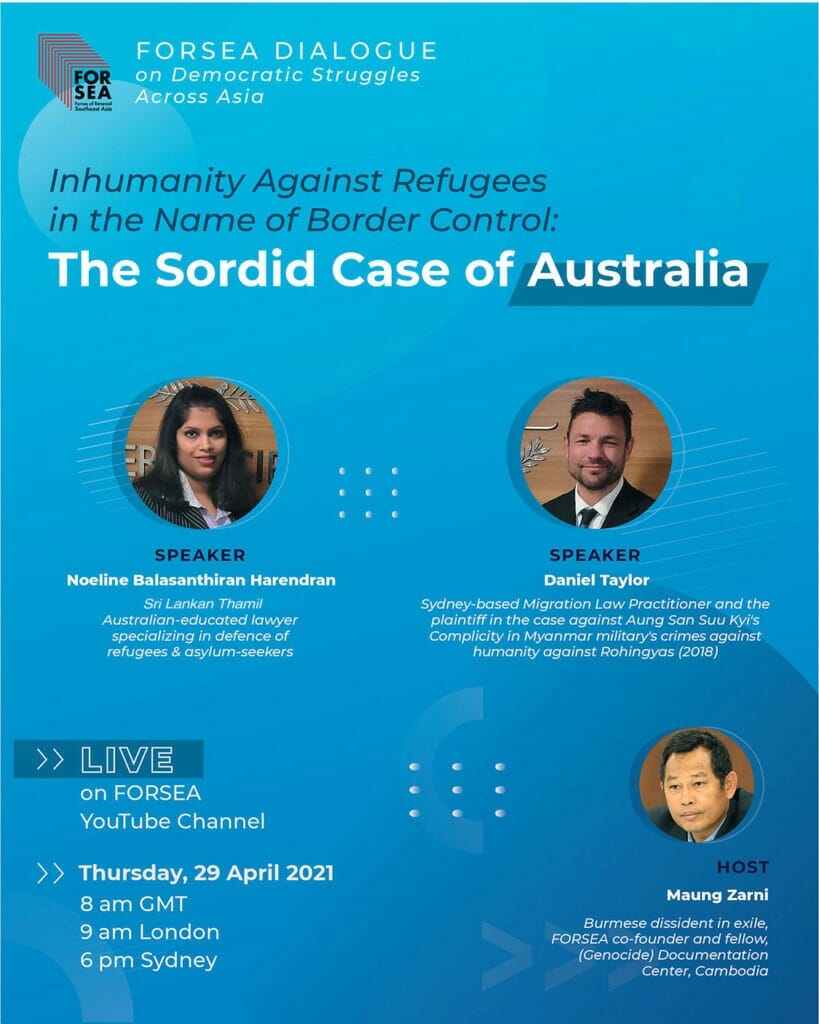

Maung Zarni, FORSEA, 30 Apr 2021

“It’s from the frying pan of wars and genocide at home, into the flaming fire of an off-shore refugee-prison complex in Australia”. FORSEA hosted a virtual in-depth discussion on how a democratic state such as Australia has adopted and institutionalized an anti-refugee policy since around 2001.

Both Labour and Liberal governments in Canberra have, with a short interregnum of PM Kevin Rudd’s government, pursued progressively war-like policies towards what the Australia media and politicians dehumanizingly call “the boat people”, or the “un-authorized maritime arrivals”.

These terms reek Australia’s white racist connotations as virtually all “unauthorized maritime arrivals”, as refuge-seekers in the waters and shores of Australia are brown and black peoples fleeing wars, ethnic persecution, genocide and terrorism in Africa, Myanmar, the Middle East and so on.

As a matter of fact, Tony Abbot, ex-Prime Minister of Australia, and now Special Trade Adviser to Britain’s Brexit Tory Government of Boris Johnson, brazenly declared “war” on refuge-seekers around 2013, having mobilized Australian Navy against this most vulnerable population, who knocked on Australia’s door, half-starved, traumatized and in desperate need of humanitarian support.

Against this backdrop, Canberra had pioneered a system of offshore processing refuge-seekers in cash-strapped South Pacific island countries such as Papua New Guinea (PNG) and Nauru, with the help of private global security companies such as G4S and homegrown Aussie companies (for instance, CANSTRUCT).

FORSEA’s guests Daniel Taylor and Noeline Balasanthian Harendren, the two Australian legal practitioners from the Sydney West Legal firm are dedicated refugee rights lawyers who fight Australia’s inhuman policies and practices whereby people who have fled genocide and torture are once again dehumanized, demonized, criminalized and locked up for no probable cause. (This revictimization is carried out by the democratic state of Australia which speaks out on human rights issues at the United Nations Human Rights Council.)

The two lawyers were joined by Ahmad Hakim, former Iranian Kurdish refugee who now runs a refugee rights campaign group out of Melbourne and Imran, a former Rohingya refugee who was transported to the infamous Manus Island “processing detention centre” where he was locked up for 5 years, despite his refugee status in Australia as recognized by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR).

Imran shared his first-hand horrific story of having been forced to live with 50 other men in one packed room without a shred of privacy for 5 years. He showed pictures of what in effect was a sub-human degraded existence in the Australian-run refugee detention centre.

Hakim relayed a verified account of a Kurdish detainee who had been severely attacked during detention at “the processing centre” in PNG: private security guards from the Australian prison-complex used zinc wire to cut the throat of Mohammad – not his real name – and coerced a horrified secretarial staff to fix the eyewitness account for the criminal act: the detainee had attempted to escape the refugee detention centre by climbing on the barb-wire fence, and by accident injured himself. Hakim showed the pictures of the victim – still in Australian captivity – with fresh wounds around his neck, front and back.

Based on the testimonies she gathered from her detainee clients – some of whom are able to speak to her virtually from their detention – Noeline painted a horrendous picture of how women, children and men are typically subjected to numerous acts of what could only be called barbarism – sodomy, rape, torture, violence, and so on. Female detainees are watched on CCTV round the clock, be they on the toilet or in the shower or in bed. Some rape victims attempted suicide resorting to all kinds of creative self-harm, including burning oneself.

Daniel Taylor talked of how inhuman and criminal – “Fascist totalitarian”, in his word – Australian state has been towards asylum-seekers and refugees and went on to explain the lucrative nature of asylum processing centres – for all those who are involved – host-partner regimes in PNG and Nauru, private companies and locals. As a matter of fact, these pioneering offshore prison-complexes are also a multi-billion-dollar business for those involved in hosting and/or managing them. The Brisbane-based corporation CANSTRUCT was paid $1.5 billion for a 5-year prison management complex with additional several hundred million, according to an investigative report by the Guardian.

Hakim and Imran explained that Australian authorities have misinformed the local populations of PNG and Nauru that several thousand detainees in their local facilities are “terrorists”. Because many are from war-torn Muslim Middle East, the Australian narrative about the detainees resonates with the widespread Islamophobia among the locals who work in these refugee processing detention centres as security guard, low level staff, and so on. Some white Australian off-shore prison staff have been spotted in Far Right rallies in Australia, according to the refugee rights campaigner Hakim.

The former refugee-cum-refugee-rights advocate Hakim observed that talking and active tough on brown and black refugees and/or asylum-seekers has been a great election winner for white Australian politicians. For such racist tough-talk has a lot of buy-ins with the largely Islamophobic Australian public who are also ill- or mal-informed about the vulnerability, rights and needs of refugees who have fled large scale misery at home. Painfully, these refugees have only jumped from the frying pan into the flaming fire of anti-refugee Australia.

Watch the discussion here.

The Australian government has been accused of forcibly separating parents from their children because they are refugees who sought asylum by boat, potentially in violation of international law.

BY RASHIDA YOSUFZAI

29 Apr 2021

Every night when Mary tucks her daughter to sleep in their home in regional Australia, the little girl asks when she’ll finally be able to see her father and siblings again.

“I don’t know what I can say,” Mary says.

“I tell her, 'They can’t come, because the Australian government won’t allow it'.”

Rohingya refugee Ali’s wife and two children are living in a refugee camp in Bangladesh but he, too, is not allowed to bring his family with him to Australia because he is on a temporary protection visa.

....

Human Rights Law Centre senior lawyer Josephine Langbien said Australia’s family migration system was “fundamentally broken” and causing immense suffering for refugee families.

“There are thousands of people across Australia who are separated indefinitely from their loved ones, because the Australian government has made a deliberate choice to use family separation to try to prevent people from exercising their right to seek safety.”

Read the full story here.